When you think of a visual novel, you probably imagine a text-based story accompanied by sprite-based visuals, usually anime-style illustrations or live-action stills. These days, however, defining the genre is a little more difficult. Evolution is inevitable, but recent indie-based visual novels have catalyzed changes in the genre significantly. While the foundational structure of visual novels have stayed intact, indie developers, particularly in the West, have deconstructed the genre and, through the rubble, have shared new perspectives.

While visual novels have only recently pierced the mainstream Western consciousness, The Portopia Serial Murder Case first helped define the genre in 1983. Created by Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii, Portopia involves crime scene investigation, NPC conversations and narrative-based puzzles. Akin to modern visual novels, the game features static backgrounds with running text and a story that only progresses once players meet story objectives in specific ways. In this way, it has the skeletal structure of its descendents, despite being released more than 36 years ago.

From then on, visual novels evolved parallel to the rest of gaming, becoming an avenue for Japanese developers to express themselves on more detailed, literary terms, free to focus on storytelling over gameplay. But standouts like 1991’s Metal Slader Glory or 1996’s Sakura Wars remained obscure outside of Japan, kept alive in the West by communities of translators, forum regulars, obsessive importers and, most importantly, genuine fans. While official translations are common today, there’s still a thriving community of fan translators, particularly on Reddit. Sites such as The Visual Novel Database have also played an important role in cataloging, preserving, and enabling discussion of the genre. Without these communities, it’s hard to imagine recent visual novels developed outside of Japan, like the indie hits Katawa Shoujo and VA-11 Hall-A, finding an audience. But if fans had the resources and passion to keep Japanese visual novels alive, what did the rise of Western indies bring to the scene?

“Visual novels from Japan, at least the ones made by big studios, have the same issue as most mass-produced media these days in every region: They are made with the intention of moving copies at all costs because of high costs,” said Christopher Ortiz, director of Sukeban Games, the studio behind VA-11 Hall-A. “This limits the themes they can explore in, ironically enough, non-pornographic titles. They need to be safe, relatable to their audience, and as a result you have a bunch of same-y games Western developers see and decide to mock.”

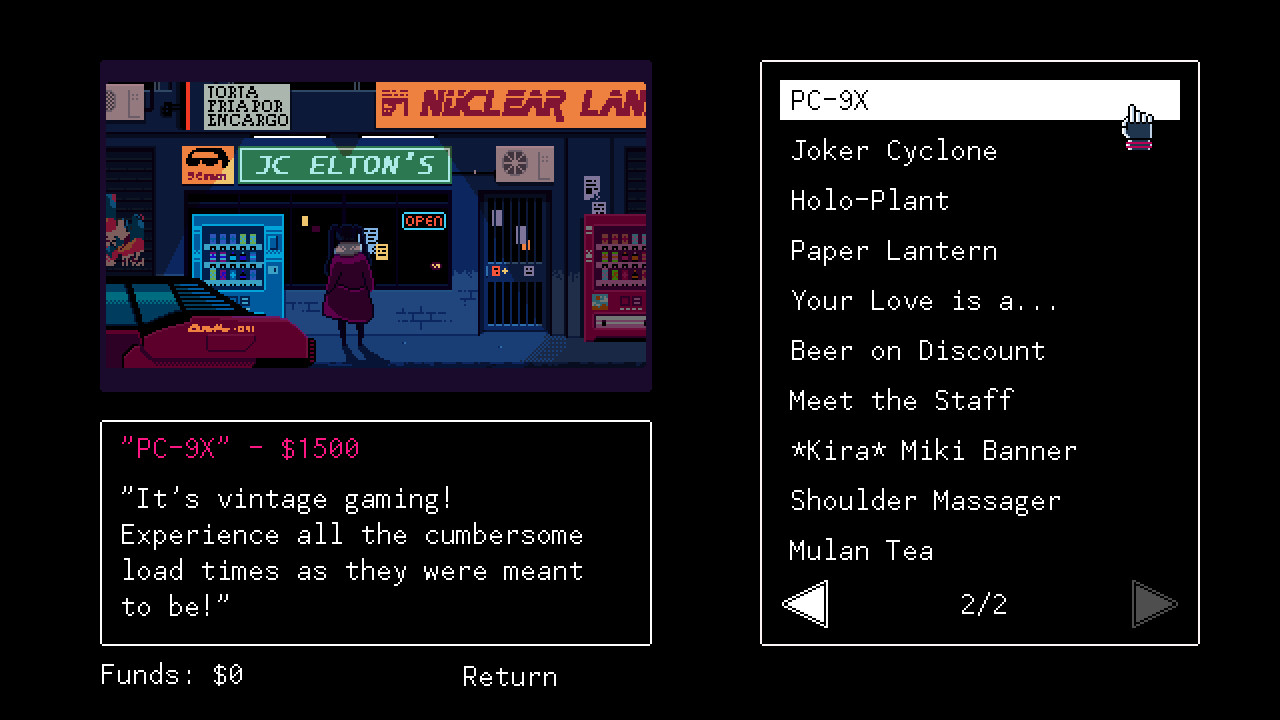

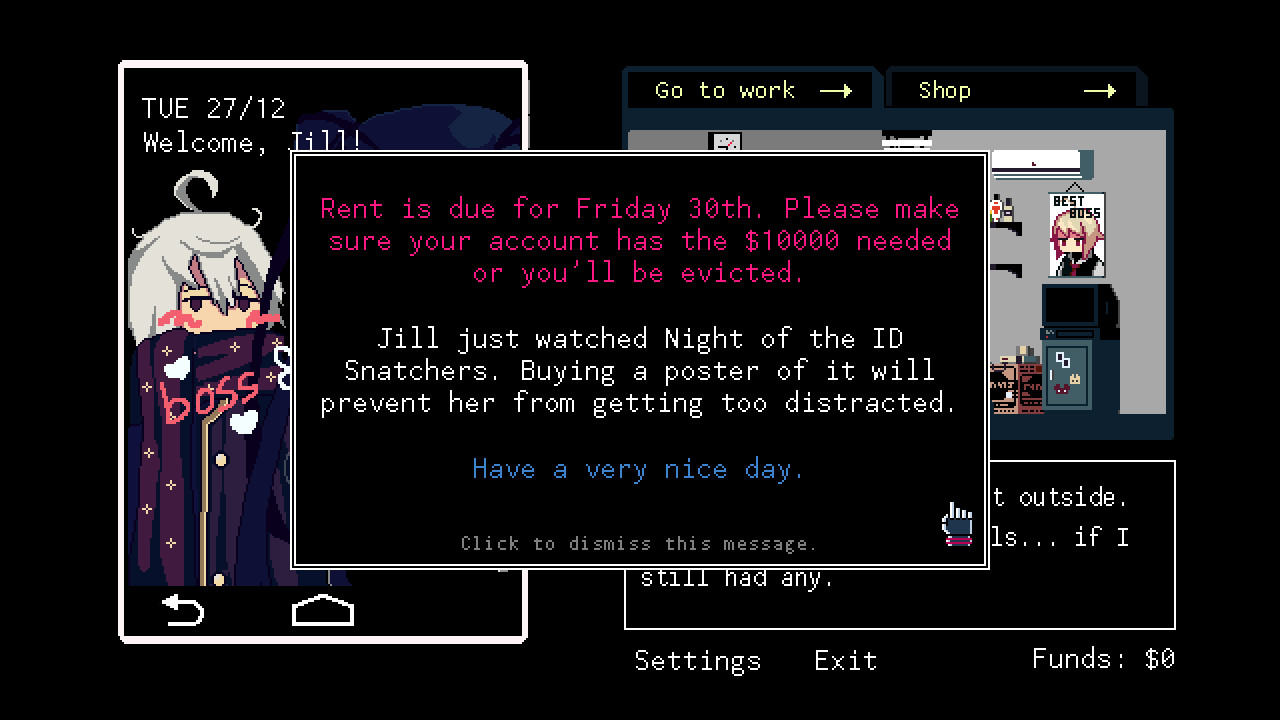

Credit: Ysbryd Games, AGM Playism

Mocking or subverting visual novel tropes, a key focus of successful Western titles such as Doki Doki Literature Club and the marketing stunt I Love You, Colonel Sanders! A Finger Lickin’ Good Dating Simulator, is a trend that has become all too common among Western visual novels in Ortiz’s eyes. He told me Sukeban actively tried to avoid that approach during development:

“[The trend is] one that’s not completely negative since it could mean creators will think about how much their project is contributing to the medium (if they have the freedom to do so anyway), but [it’s] also incredibly tiresome since it makes some customers only crave these types of disruptive visual novels from a genre they didn’t play a whole lot anyway.

“From a hopefully not-arrogant point of view, I think VA-11 Hall-A managed to grab this audience that’s looking for something that speaks to them without coming from a cynical mindset that every visual novel is a dating sim that deserves to be parodied, and it is my hope that more indie visual Novels from this side of the world come from the same place after seeing the success of VA-11 Hall-A.”

Credit: Ysbryd Games, AGM Playism

Freedom from the economic pressures of the Japanese market, in Ortiz’s view, allows Western studios to take a different approach to the genre. As such, indie development has become a pathway for visual novels to grow, bringing in fresh perspectives.

These new perspectives come in two forms: narrative and gameplay. VA-11 Hall-A shone by blending a unique combination of different mechanics with an original take on the cyberpunk aesthetic. By mixing bartender-based gameplay with the narrative choices of a visual novel, the game was able to iterate on a familiar formula. VA-11 Hall-A feels more “gamey” than other visual novels simply because it adds more traditional, systemic gameplay to narrative choice. Other visual novels, such as Zachtronics’s Eliza, brought new facets to the genre by touching on topics foreign to most other visual novels.

Matthew Burns, the writer for Eliza, strongly believes in the place indie visual novels have in changing the genre’s narrative. “If anything has changed in particular with today’s English-language visual novels, I think a lot of what’s happening with visual novels now is an expansion of the types and kinds of stories being explored,” Burns said. “Personal stories, queer stories, native stories like When Rivers Were Trails—and that’s great for the medium in general.”

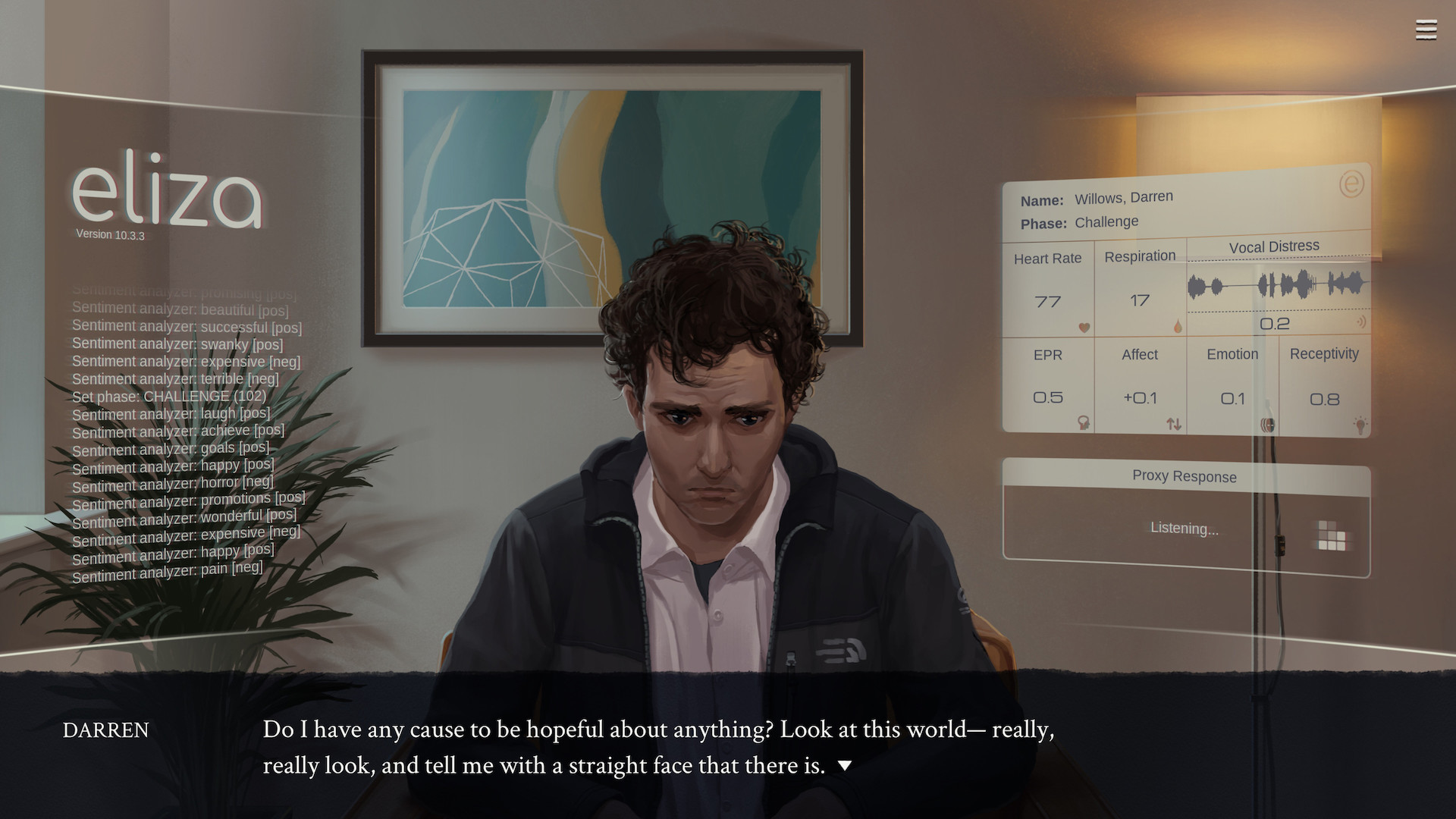

Credit: Zachtronics

While some of these stories are being told in Japanese visual novels with bigger budgets, none have the freedom of expression as games like Eliza, a take on artificial intelligence that hasn’t been explored in the same depth beforehand. The game tells a story about counselling software, negotiating modern concerns within the visual novel framework. It’s easy to see why Burns believes the genre is akin “to classic literature” thanks to the volume of writing it allows for. Instead of worrying about how gameplay could enforce story or how to interweave it, a visual novel allows for more textual expression.

Burns found buckets of inspiration in Japanese visual novels, despite the difference in their intended audience. The Danganronpa series, especially, “showed [him] how much of a kinetic feeling you can achieve in the visual novel format.” Other visual novels that inspired his writing were the “deeply personal, yet utterly hilarious” Butterfly Soup and the “highly entertaining” titles We Know the Devil and Heaven Will Be Mine. While indie visual novels exist in a space relatively free from the expectations of mainline visual novels, they are still, to some extent, indebted to them. Western efforts enable a kind of intertextuality between different cultures and scopes, allowing writers like Burns to express themselves in that space between.

While speaking to Burns, he brought up an interesting point where Western story-based games and Japanese visual novels converge: graphic adventure games. Visual novels, in his view, “really grew out of graphical adventure games which were pioneered simultaneously in Japan and in the West, a lineage you can see in games like Snatcher.” Developed in the late ’80s by Hideo Kojima, Snatcher blends elements from visual novels and Western adventure games together, much akin to modern indie efforts. The story has some touches of a visual novel in there, along with point-and-click and first-person-shooting elements. In some ways, genre-defying visual novels, especially from the West, may simply be picking up from where games like Snatcher left off, a place where Japanese and Western design mingled.

VA-11 Hall-A, too, had a list of games Ortiz drew from for inspiration, namely The Silver Case, Collage and Analogue: A Hate Story, three visual novels which, in his eyes, “feel realistic despite some of them having either sci-fi or surreal elements.” Combined with their realistic feel, the trio impressed Sukeban Games thanks to their ability to “shift the presentation and explore more than just one medium, look extremely unlike everything else in the genre, and tell stories from a more humane point of view without resorting to cheap storytelling devices or settings.” Despite these influences, though, VA-11 Hall-A feels wholly original, mostly due to the risks Ortiz and Sukeban Games made during development.

However, while indie developers are free from the potential shackles of mainline Japanese development, they’re starved of the resources, too.

“I still think we are a bit behind when it comes to production values. I don’t think there’s a western visual novel right now that could be considered competition to the likes of Steins; Gate or pretty much anything Nitroplus makes,” Ortiz conceded, though he admitted it “would be cool to see a massive visual novel project being born in this side of the world.”

Credit: Spike Chunsoft Co Ltd

Gameplay-wise, VA-11 Hall-A is an intoxicating mix of visual novel and bartender sim, presented in a PC-98-inspired cyberpunk aesthetic. Players assume the role of the bartender at the eponymous watering hole. Despite being nice to look at, the futuristic world of VA-11 Hall-A is distinctly dystopian, with all facets of society is controlled by megacorporations. Everyday life is defined by nanomachines, which infect the majority of humans and determines what they can and cannot do. Every night, some of the fascinating residents of this world stumble into the bar, where players can converse and decide on which drinks to mix to become privy to the latest secrets from the seemingly watertight dystopia—and, in the process, make genuine human connections.

Unlike most visual novels, the game’s only way of communicating with patrons is through the mixing of drinks instead of making conversation-based decisions. By a subtle act of substitution, VA-11 Hall-A managed to stick somewhat to the visual novel format while offering gameplay that felt different. The world, though, despite being heavily inspired by anime, Policenauts, Snatcher, Shin Megami Tensei and vaporwave, is rooted in the turbulence of Venezuela, particularly the 2014 protests.

Despite a lack of resources, VA-11 Hall-A endeavoured to be different and succeeded in doing so. “Since we were two Venezuelans without a lot of money back in 2013, a visual novel always seemed like a no brainer for us. It would allow us to explore simple mechanics while keeping production scopes small enough to finish in a sensible timeframe,” Ortiz said. “[The challenge was] pretty much everything outside making the game itself, such as our challenging daily life as a result of living in Venezuela, as well as other personal issues we went through as a team.”

Credit: Ysbryd Games, AGM Playism

The “daily life” of Venezuelans was particularly taxing, with some aspects of the creator’s lives being directly translated into the game’s dystopian undertones—particularly given the hyperinflation, civil unrest, and chronic shortages of basic goods the country endured during development. The characters in VA-11 Hall-A, no matter where they fit into society, are always affected by the reach of a government that is failing them. But compared to more intense real-life moments—such as when a close friend had to jump from rooftop to rooftop following the protests of San Cristóbal—VA-11 Hall-A, even in its most dystopian moments, is a bit more laid back.

Eliza is likewise rooted in and inspired by real-world issues that haven’t been discussed in mainline visual novels. Reflecting on the origins of the game, Burns revealed it was inspired by research on post-traumatic stress disorder:

“The original idea came in 2014 when I was working for a major university. I witnessed a demo of DARPA-funded research with the goal of screening returning American soldiers for PTSD using a combination of computer vision, real-time analytics and virtual human avatars. It struck me deeply and I began to think about creating a story inspired by it.

“A few years later, as we were finishing up Opus Magnum, I mentioned to Zach [Barth, founder of Zachtronics] I was writing a narrative game about a ‘virtual therapist.’” Zachtronics had become well-known for its unique puzzle-based games like Opus Magnum and Exapunks, which blend narrative with deep gameplay systems. Eliza was somewhat of an outlier, being more explicitly narrative-focused. “Zach was interested in the idea and decided it was time to try something new. He offered to produce the game as a Zachtronics title, combining the original concept, writing, and music with art from the studio’s art team and the resources to record voice actors.”

Credit: Zachtronics

The result is a visual novel that not only tackles the delicate nature psychology and counselling but the future of medicine and the remits of AI-backed solutions. By existing outside of the AAA space of visual novels, VA-11 Hall-A and Eliza have both managed to bring new perspectives to the genre from the fringes.

While there is a clear respect for Japanese visual novels in this scene, indie developers are still facilitating change. By casting away some of its tropes for the sake of evolution, indie games like these inspire change. While they may not have the exposure of bigger studios, these games, perhaps accidentally, allow for new, important stories to be told simply by operating under the radar.

At least now, more indie developers have an opportunity to tell the stories most important to them. As Ortiz said, “It’s fucking hard, so all you can do is pour your heart into it.”

Header image credit: Zachtronics

Digital marketer by day and freelancer by night, the first game Ben ever played was Donkey Kong Country on a dusty SNES. He’s been obsessively playing, discussing and, most importantly, arguing about games since. After completing his degree in English Literature, he thought it’d be a pretty good idea to write about games, too. He mains Donkey Kong in Smash (obviously).