The pop of a precise headshot downing a foe. The clang of a perfect parry leaving your opponent open to a vicious counterattack. The satisfying snap of the lootbox prying itself open in an ornate dance of cogwheels and clockwork to reveal the glowing horde within. These are phenomena that video games have reproduced to the point to absolute mastery, and for good reason. These mechanics and their accompanying spectacle are the hooks that savagely dig into the psyches of so many gamers, proven to reliably bring in cash hand-over-fist when executed at a high level. Because they appeal so universally to such a wide swath of the gaming populace, these elements have been polished to a high-sheen by the crunching, irrevocable progress of capital, which usually leaves human wreckage in its wake.

Still, these critical aspects might grab the players, but they’re vastly outnumbered by the more mundane building-blocks of modern games. Many game developers spend the majority of their time fiddling with the invisible bits, the parts that aren’t supposed to draw attention to themselves. But of these many unsung elements, none is so maligned or as misunderstood as the humble video game ladder. Now that the ultimate in ladder-carrying simulators has burst onto the market in the form of Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding, it’s worth examining why they’re so widely maligned.

While it’s easy to offer a glib comment or two on Kojima’s perennial goofiness, when it comes to ladders, there’s no doubt that Death Stranding is on the top of the heap. Since the game is all about painstaking navigation through unfriendly terrain, the player relies on ladders to traverse not just vertical spaces, but to bridge the gap over chasms and safely cross rough waters as well. Since the buildings you set up can be utilized by your fellow players—who can then choose to “like” it, raising their porter grade—Death Stranding offers more opportunities for creative ladder construction and cooperation than any game before it.

Credit: Sony Interactive Entertainment

Even still, think about it: have you ever encountered a good video game ladder? I certainly haven’t. While your answer might vary, I’d argue the question is loaded in itself: There’s no such thing as a critically-acclaimed gaming ladder, just in the same way that we don’t give out awards for “best matchmaking” or “most stable game.” While truly hardcore fans might remark on these hyper-granular details in a game’s subreddit, for the most part, if a writer mentions a ladder in their 1,200-word review, it’s usually not to praise it. In essence, the ladder is a perfect metaphor for how video games are still figuring out how to depict the more mundane aspects of our lived experience, even as we harness the newest technology to deliver the latest and greatest in glittering escapism.

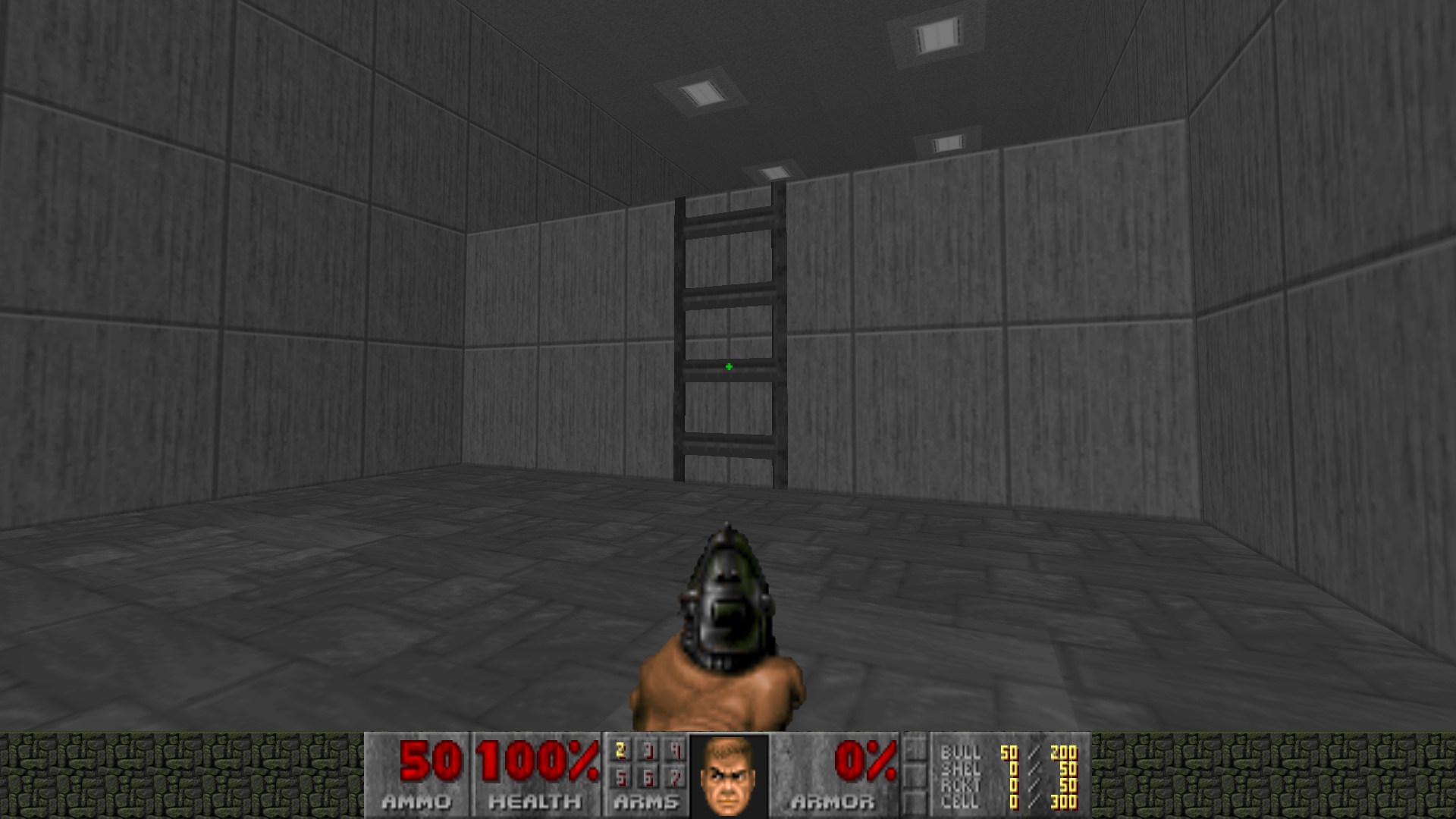

Back in the era of 2D, classic arcade games like Donkey Kong and Burger Time relied on simple ladders to power the player’s traversal around large, open areas. Such mechanics were relatively straightforward to implement, necessitating only the creation of a few new sprites to supply the main character’s climbing “animation,” as well as the ladder itself. But as video games have arced towards the realm of realism, resulting in gradually more “immersive” experiences over the past three decades, they’ve also exhibited a complicated relationship with everyday fixtures like ladders. During the beginnings of the first-person shooter as a genre in the early ‘90s, primitive computer games struggled to convey the concept of verticality in any capacity. Levels in progenitors like Wolfenstein 3D are flat collections of corridors that resemble the mazes you might find on the back of a cereal box, with “elevators” serving as the exits. (They don’t actually function, of course; the loading screen for the next level gives the illusion of movement.) The epoch-defining Doom finally introduced stairs into the mix in 1993, followed by the truly 3D Quake in 1996, but instead of building an entirely new object for upward movement, mappers created their own clever solutions to the problem.

“In the early days of FPS, ladders were totally a technical novelty,” said Breadman, a longtime mapper and modder in the genre. “If you look at older games based on the Quake engine derivatives, you’ll notice designers make use of teleporters, lifts, and stairways to elevate the player. It’s probable that the concept of ladders in those times was a bit of a technical challenge, and they were thus rarely seen. Doom tried to make ladders occasionally. These were made by using very tiny steps – essentially squashing a staircase. It’s clear the idea was there, there just didn’t seem to be an elegant way of executing it.”

By his own admission, Breadman knows a lot about video game ladders, and it’s not hard to see why. He’s been working in GoldSrc—the engine that powered the blockbuster FPS Half-Life—since the game’s release in 1998. At the time, all of the climbing and jumping across crates and ladders in Valve’s freshman effort made it feel like a generational leap over the muddy sci-fantasy milieu of Quake; from the vantage of 2019, however, the flaws are apparent. In Half-Life, while attaching yourself to the ladder is simply a matter of walking up to it in, you climb comically fast can fire even two-handed weapons while mounted. These quirks are more charming than damning, but one is particularly galling: Trying to mount the climbable surface from above requires a degree of finesse that doesn’t come naturally to those raised on more modern games, and one missed footfall can lead to your untimely demise. Eventually, after dozens of hours playing Half-Life-mod-turned-retail-game Counter-Strike, I perfected my personal “leap of faith” technique: jumping out over the ladder, turning around, and grabbing it just before I hit the ground. It was far from intuitive, but it worked (almost) every time.

However, while Half-Life and its sequel might remain infamous for their finicky climbing, the advancements that replaced them didn’t so much solve these problems as replace them with a whole new set of annoyances. As Breadman puts it, there are two major types of ladders in games: ones that allow you to “glide” up and down them while performing other actions, and those that require you to “lock” your character into a predetermined animation. While the resulting visuals usually looked a lot more believable than the incessant ladder-humping of Source engine games, the pace of the climbing suffered as a result, which made long ladders objects of utter tedium. “F.E.A.R used lock-in ladders, which I feel kind of added to the sense of realism,” Breadman said. “The player is vulnerable whilst mounting a ladder. That was an overlooked aspect of DayZ. If you really wanted to kill somebody and be safe doing it, you could wait for them to climb a ladder. Highly situational, obviously.”

To Joe Dykstra, a level designer at Rockstar Games, the historical issues surrounding ladders exemplify a greater shortcoming in triple-A games. It’s reached the point where more irreverent games will use ladders as a punchline. Dystra recalls a gag in the cult indie RPG LISA—one of my all-time favorite games—where a sign tells the player that there’s something “very important above.” Reaching the top requires two full minutes of rope-climbing, where the player finds nothing but a disembodied hand with its middle finger raised. The game doesn’t even let you jump off the ledge to your death, either. (The fact that unique music plays as you ascend seems to suggest this entire section is a parody of an infamous ladder-climb in Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater). While designers and artists pour in a huge amount of effort into making sure that even minor animations burst with verisimilitude and personality, the actual feel of performing mundane acts such as climbing can suffer as a result.

“This results in slow sequences breaking up the action, and a lot of waiting while you watch your character grab rung after rung with little to no input,” Dykstra said. “The areas we’ve improved as an industry have mostly been in the ease of entering and dismounting them, where usually it’s much more responsive than the old days.”

As Dykstra sees it, rather than imitating the now-standard “lock” tradition, different games should implement their ladders in ways that complement their strengths. For example, while the Source-based Counter-Strike: Global Offensive still boasts the style of climbable surfaces that have drawn so much criticism over the years, Dykstra argues that it suits the style of game. Sure, while it’s far from “realistic” to watch a combatant in full Kevlar fly up a ladder while firing his M4 at faraway opponents, players in Counter-Strike don’t start limping when they get shot in the foot, either. “This is a conscious choice made by developers, because these games are competitive shooters that need to prioritize simplicity and clarity of control over making them look or feel more realistic,” Dykstra said.

This illustrates perhaps the fundamental truth that underlies all of this discussion: While mundanities such as ladders might feel like a minor, even vestigial aspects of a massive big-budget production, they can actually have an outsized impact on how a game plays. For example, back in his formative days as a Source modder, Dykstra recalls putting much care into the positions of ladders on his zombie maps, knowing that they were likely to serve as chokepoints for escaping survivors. When it comes to strategy games, like Firefly Studios’ “castle sim” series Stronghold, special units like the “Laddermen” can use their eponymous tool to climb your foe’s walls, and determining how they behave can have a huge effect on game balance.

Credit: Valve

“From a developer’s point of view, ladders are a place of transition,” said Simon Bradbury, a designer at Firefly. “It’s somewhere that the normal rules don’t apply, given that an immense amount of work is needed just to build this base game experience. So, it’s easy to see why devs often don’t put enough work into this area. The worst crime that they can often be guilty of is speed-of-use. They can really inspire dread in players if actually using them slows the action down too much.”

While all these designers admit that ladders in games could still use a host of improvements, it’s Dykstra that said it best: “What makes ladders and other similarly intricate and specific interactions in games difficult is the granularity and small scale of the interaction involved in performing them. Climbing a ladder in real life often takes nearly all of your attention… none of this granular level of detail exists in most games, often with good reason, because smaller, basic actions in many genres are expected by players to be taken care of automatically, as they are much less important than focusing on the core gameplay loops…”

For all its flaws, Kojima’s avant-garde hit Death Stranding is one of the few games that doesn’t automate those basic interactions, asking you to micromanage even the very act of walking and climbing. It’s a divisive decision, but one that gets at the very heart of what makes video games so unique—and sanding down the drudgery of everyday life can cause us to forget that sometimes. So, next time you’re spending thirty seconds staring at your phone as your meaty murder-man climbs up a ladder, think about the designer who put that together. It’s a miracle that anything works.

Header image: Death Stranding, Sony Interactive Entertainment

Steven T. Wright is a reporter and novelist living in the Twin Cities. He is the former independent games columnist for Variety, and he has written for Rolling Stone, Polygon, Vice, and many others. He almost named his novel after a city in Final Fantasy, but his friends talked him out of it.